“Confinés”: French for “quarantined”

The life of a family of five during the COVID-19 crisis is understood in any language

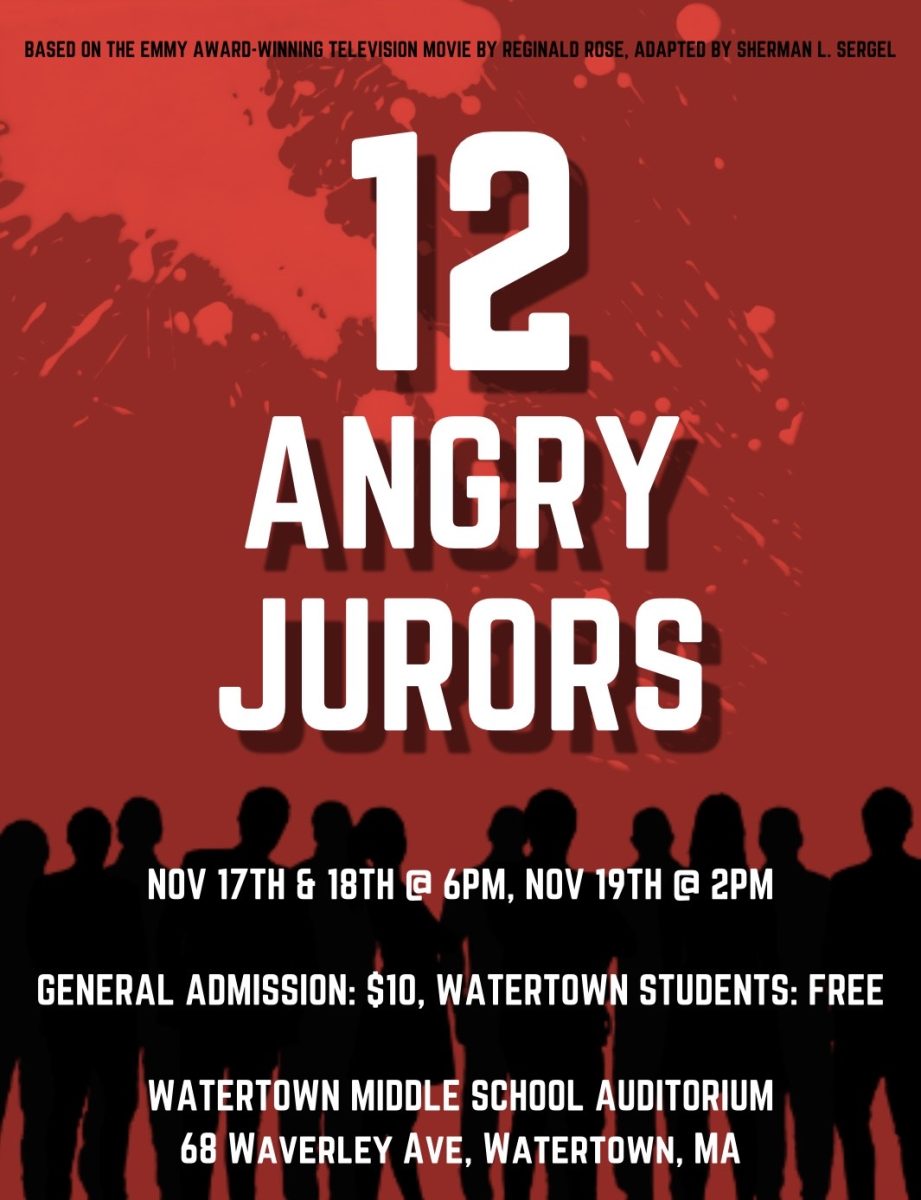

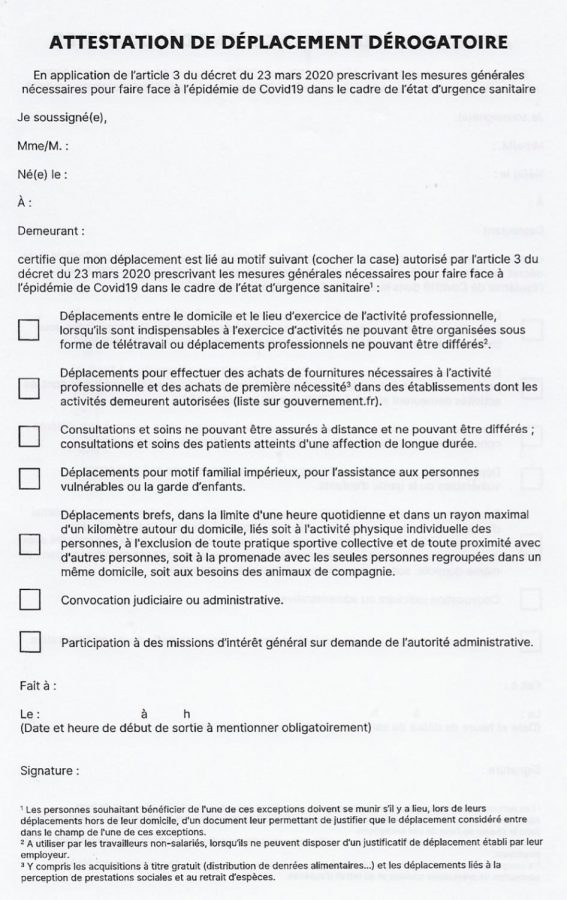

Raider Times photo / Courtesy of Florence Deguyenne

Florence Deguyenne poses with her parents, father Franck (center) and mother Huong (right), in Orléans, France.

May 10, 2020

Florence Deguyenne, 17, is sitting at home on Facetime while her brother, Nicolas, is doing a home workout in his room upstairs. Their mother, Huong, prepares their dinner after coming back from the family restaurant like every other night during the coronavirus lockdown. Florence’s father, Franck, comes home late from his job as an IT specialist, ready to have a nice dinner with the family just as Florence’s other brother, Fabrice, comes out of his room after playing his 100th PlayStation game with his friends, bored from not being able to go outside.

This may seem like a typical American quarantine family situation, but in reality, this family lives all the way in Orléans, France.

This French family, like many others in France, Spain, and Italy, are experiencing a total lockdown due to coronavirus, not allowed to go outside and roam the streets, just like us Americans have the pleasure of doing. In France, there is a national quarantine order that forces people to stay at home.

Safe to say, France is taking the coronavirus very seriously, even though France only, relatively speaking, had 138,854 confirmed cases and 26,310 deaths as of May 9, according to the French government’s numbers, compared with the whopping numbers in the United States: 1.274 million confirmed cases and 77,034 deaths, according to the CDC.

To best get a sense of the effects of a forced quarantine order, it is best to first step into the quarantine life of Florence. If you ask what one of us teenagers does here while stuck at home, you would likely get a similar answer to Florence: “I listen to music, watch videos and TV shows and movies, and I use social media, too. I also talk to my boyfriend [that’s me!], and I eat.

“I take time to sleep. I am sleeping more now than before we were required to stay at home. In general, I take more time for myself, not for school.”

Florence, who spends a lot of time with her friends and large extended family, went on to say, “I can’t hang out with my friends and that’s so sad. And I walk so much less and less outside. When I’m outside it’s only in my backyard, and that’s different than going out.”

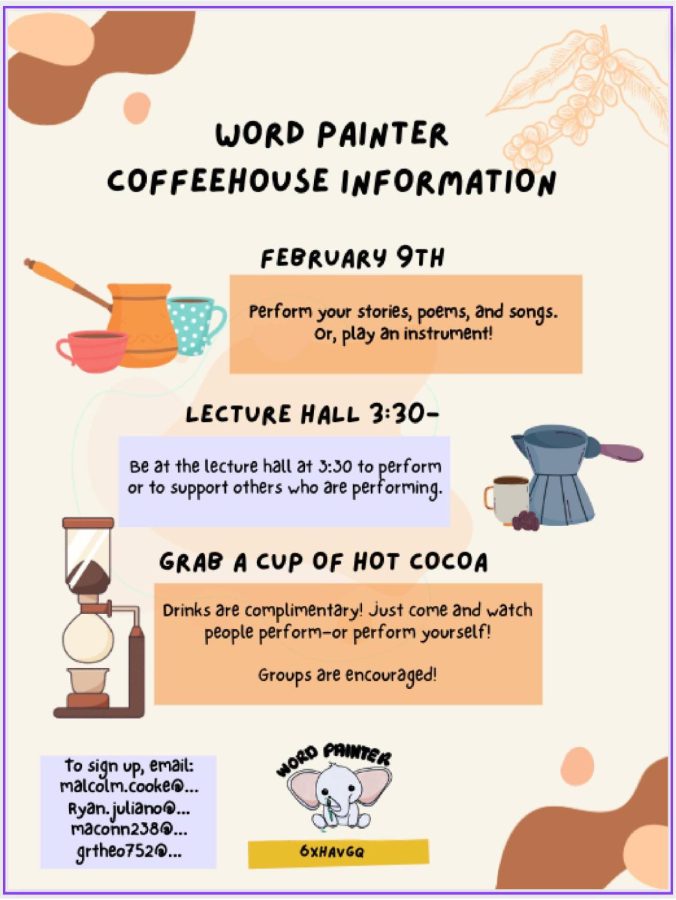

OK, it is not being entirely truthful to say that they are not allowed to go outside at all. In reality, a household has to buy food, go to work, exercise, and the country has to continue to be run effectively. In order to go outside, all French citizens are required to fill out a form in which they select one of seven specific reasons to exit the home, sign it, and take it with them outside.

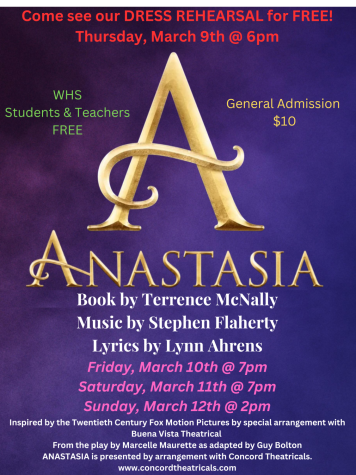

For people to go outside in France, they need to complete this form, and satisfy one of the government’s seven reasons.

For those of us who do not speak French, here is a basic translation of the form (courtesy of the French government website):

Name:

Birthday:

Address:

Option 1: to go to work, if remote working is not possible

2: to buy essential supplies at authorized local shops

3: to go to a medical appointment that cannot be postponed or carried out remotely; or for treatment of a long-term health condition

4: to take your children to daycare or to take care of an elderly person

5: to take exercise individually or to walk with members of your household, within a kilometer of your home and for no more than one hour (this option includes walking pets)

6: to respond to court or administrative summons

7: to join missions of public interest at the request of the administrative authorities

Date:

Time:

Signature:

French police stop pedestrians in the street and make sure they are outside for one of these seven reasons, so it is important to adhere to the rules. People who do not have this form when outside are liable to be fined up to 135 euros ($146), and another 245 euros ($264) if not paid on time.

“Most people don’t go outside at all,” Florence said. “My friends and I stay home a lot so we don’t ever have to deal with the form.”

Like Florence, many of her friends and family cited watching Netflix and videos, and also playing video games to pass the time. Such is the case for her 16-year-old brother, Fabrice, her 20-year-old brother, Nicolas (pronounced “Neecola”), and three of her friends, Mehdi (pronounced “Med-ee”), Tristan (pronounced “Tree-stahn”), and Sonia. It quickly becomes obvious that life in quarantine does not provide itself to being a time where one can really do anything normally thought of as unique or interesting.

Moving past just passing the time, a major part of the life of American teens during the coronavirus crisis is online school, and this is no different in France. Like us here in the United States, French online classes are not ideal, as Tristan sums up for everyone: “My online school is not very good.”

Florence’s brothers both said that the teachers “are not well-adapted to the system [of online teaching].” It is important to note that Nicolas is in college, so the problem of poor online teaching is not just present in high school. This makes it hard to learn effectively, as Florence noted: “It’s harder to understand when the teacher explains something.”

She also said that she is “not used to having classes on a device,” making the disconnect between the student and teacher even more apparent. Also, another problem with learning online is that “it’s hard to concentrate,” according to Sonia, who is not used to having to work totally by herself instead of at school.

Florence Deguyenne poses on a trip to New York from France with members of her family, Nicolas (left), Fabrice (second from right), and Huong (right).

One difference between French schooling and American schooling is a large test at the end of the French senior year (en terminale in French) called the Baccalauréat, or Bac (pronounced the same as the word “back”) for short. This test covers every subject learned in school and is basically a college entrance exam, since most colleges in France use it as a defining measure of students’ aptitude in the admissions process.

This year, due to being forced to stay at home, the French Ministry of Education (Ministère de l’Éducation nationale) canceled all Bac tests besides the French oral subject test. Since French college admissions are so tied to the Bac, Bac tests for French high school graduates are now “validated from the notes in the school book,” according to the Bac government website, which is another way of saying that students’ grades throughout the year will be translated into a Bac score.

This is not a welcome change for Florence.

“It’s just unusual and changes my plans to study for the Bac,” Florence said. “It changes the goal of studying to pass it. I’m disappointed because I’ve studied for it and I was less focused on my courses during the year [but instead was focused on studying for the Bac]… so the grades that I will have will not be what I expected.”

Tristan and Sonia have similar thoughts, and Sonia added that “people who cheated [throughout school] don’t deserve it.”

Besides school, work is a large part of people’s lives in France, just like almost everywhere else in the world. Huong, Florence’s mom, has owned the small Deguyenne family restaurant, Indochine 45, for many years, and the coronavirus has affected the business greatly. Under normal circumstances, Huong manages the restaurant and cooks alongside a chef, and Nicolas, along with a part-time waitress, works the 14 tables.

The staff of the restaurant are all close to the Deguyenne family, along with their loyal customers who come to chat with Huong. However, this all changed once the quarantine order was put in place along with the order to have no on-site dining, just like in the United States.

“We can plan anything, but we need to work,” Huong said. “For now, it’s very hard… but I hope it will be OK.”

Like many other restaurants, Indochine 45 has faced a large loss of clients.

“We need to change our strategy,” Huong said. “We will change to something new to attract clients better. It’s really hard. We all have to wait, but personally, I like to work, and now I work a lot more because I don’t have employees.”

Florence Deguyenne (second from right) hanging out pre-quarantine in Orléans, France, with friends (from left) Armand, Mehdi, and Tristan.

This hard-working mother said that she is “very occupied at home, at work, and cooking,” but she stays positive.

“Everything is trop bien [super good],” she said of her kids.

Huong has received 2,500 euros ($2,700) from the government for businesses that have been hit hard by the coronavirus crisis to be distributed to her employees, along with 1,500 euros ($1,620) for her own personal spending.

“This is a compensation for what she could have earned since all restaurants had to be closed [for on-site dining],” Florence said.

This money helps sustain the family’s and restaurant’s finances during this very tough time.

Franck, Florence’s father, works as an IT specialist in his employer’s office building. Like Huong and the millions of French and American workers, Franck’s job has been affected because “a lot of [his] colleagues stopped [working].”

He mentioned that they “need to introduce teleworking for my coworkers. There are some of them who can and there are some who can’t,” but interestingly, he said that “nothing changed besides that.” This is good for him and his family, since every sense of normalcy that one can have during this time is helpful.

Of the company he works for, he said, “they produce less,” but also that “for now it doesn’t affect us because our field of work is to assist the users, so the users still work from far.”

Mehdi, 19, lives on his own and works at the multinational retail supermarket chain Auchan (pronounced as “oh-shaun” with a very soft n). Mehdi said the coronavirus hasn’t affected him specifically. About work, however, he said that “there are less people,” but he also received “a bonus of 1000 euros [$1080]” for the month of April. This is similar to many compensation plans for stores in the Boston area. For example, Shaws gives a bonus of $2 extra per hour, an employee said.

Despite the fact that there are less people working at Auchan where Mehdi works, he noticed that “the store’s revenue is almost the same.” Like in the United States, there are social distancing guidelines that the French government has put out. However, Mehdi said, “there are probably 40 percent of the clients who wear masks. Besides in checkout, the social distancing is not respected. I can see that in the aisles people are still close to each other.”

As of May 8, the quarantine order was to be lifted by the government on May 11, and people will be allowed to go outside, certain businesses will reopen, but gatherings will be limited to no more than 10 people.

At the time of interviewing everyone, it was uncertain whether or not the quarantine was to be extended past the May 11 deadline.

“I think we will stay quarantined until July because the peak is not already here and that would be stupid to not be quarentined just because the peak has passed,” Florence said.

Nicolas echoed her idea by saying, “I don’t think it will end on the May 11 deadline. If we want it to be on May 11, we need the curve to flatten… but I hope [it will end] soon.”

No matter when anyone thought it would end, everyone would be happier if everything went back to normal as soon as possible, and Huong summarizes this for everyone by saying, short and sweet, “I hope soon.”

–May 9, 2020–