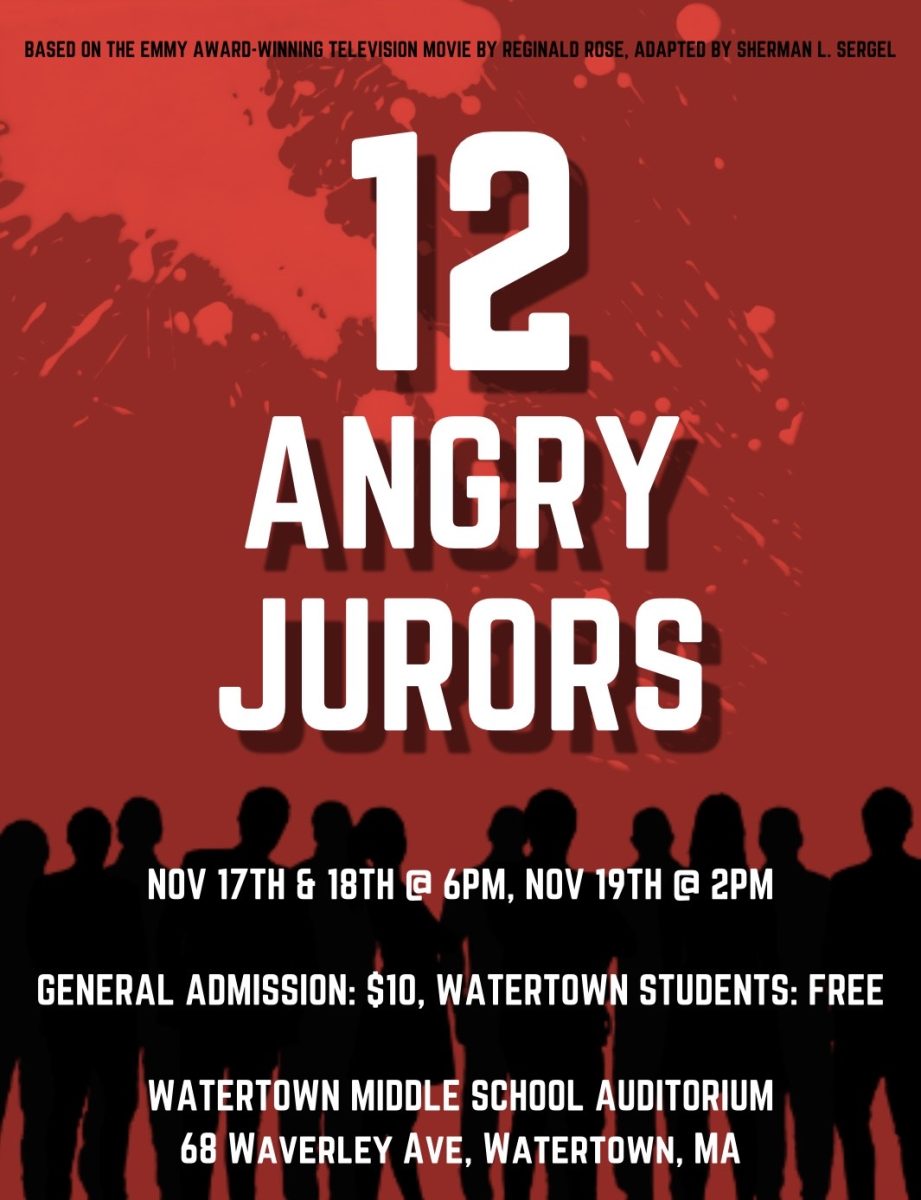

Asking for your vote because I can’t yet

Going door to door in N.H. shows a campaign worker a different side of the political process

Raider Times photo / Jeremy Ornstein

The author poses at the Nashua, N.H., office for the Hillary Clinton campaign.

October 5, 2016

The best thing about canvassing in Nashua, N.H., is the colors. The blues are certainly part of the draw: light, dark, navy, cotton candy, azure. The Democratic candidates have signs and stickers in all different shades of blue. But at the end of the equation, it’s not just the blues that brought me all the way up to an entirely different state. Rather, it’s the reds, oranges, and yellows.

I’m a nature-oriented person, and seeing leaves change with the seasons is one of the grandest sights my eyes have seen. Normally, leaves change in late September and October. This year is not like any other year, however; much of Massachusetts is experiencing an extreme drought, and the loss of water is forcing trees to abandon their leaves earlier than normal, even as far north as Nashua.

Driving up Route 3, the trees gradually change color, as if a brilliant lighting path at an airport. But the trees fade away, and buildings pop up into their place as Nashua emerges.

I drove to New Hampshire in a carpool, with a man named Ted Grossman. He’s a jewelry salesman from Newton, but he spends his time and passion in Nashua, volunteering for Hillary Clinton.

My friend Zev rode with us, too. Zev is a bright-eyed freshman in high school, but no reasonable person would be misled by his innocent looks: he’s an expert canvasser, and has been on the political scene since he was 9 years old. I would be canvassing the doors with him, and I was glad to have such a dependable partner.

When we got to Nashua, we parked and went inside the Nashua branch headquarters. The office was full of color, with the walls covered in old campaign signs and edited Hillary pictures. All of the staff were nice, albeit incredibly stressed. My point man there was named Abraham. When I talked with him on the phone, his voice made me imagine a big, burly man. In person, however, Abraham was soft spoken, slight, and utterly capable. Other campaign workers included Katie, the blonde Brit who is nothing if not nice, and Leah, who is always, always, talking with someone.

After waiting for some time, we began to wade into the crowd to find our “turf” materials. Canvassing, for those of you who don’t know, is the process by which campaigns are successful and candidates win elections. In other words, it’s what volunteers do when they walk around knocking on doors, talking about their candidate, and handing out pamphlets or literature.

They only knock on certain doors, the doors of the people on their lists — because campaigns are all about efficiency. They don’t want their volunteers knocking on anyone’s door and asking them to vote. Rather, the campaign tries to come up with lists of registered voters, who have a chance of voting for its candidate.

Before anyone can do any of that, however, volunteers need the lists of who they are canvassing and maps of where they can be found, along with check boxes to mark off their target’s responses.

The papers usually come in a jumble, and if you aren’t organized, by the end of the canvass, you won’t be able to find anything you’d want to. (Thank God, that Zev is organized!) When we finally got our materials, and got back onto the road. Ted dropped off Zev and I at one side of the turf, and he went to the other side; the plan was for us to meet up in the middle. Off we went!

The first thing you realize as a canvasser is that the activity has the potential to be incredibly boring. It requires a huge amount of walking between the homes on your list, lots of knocking on doors and ringing doorbells, and many papercuts from the dozens of pieces of literature that you lug around on your journey.

At the same time, canvassing makes me feel powerful. I can’t vote. I’m not old enough. But by knocking on doors, by changing the minds of a few voters, by pushing a few more people out to the polls, I am literally changing the course of an election.

It can be tedious, and it’s definitely difficult to keep it up, but the power that I am seizing through my actions makes it worth it to me.

You also get to know a community through canvassing. In fact, I got to know more of my neighbors through canvassing than through anything else.

The author poses with a cardboard cutout of his candidate at the Nashua, N.H., campaign office.

In Nashua, the houses were all spaced fairly far apart. In the part of Nashua that I canvassed, there wasn’t really any homogeneity regarding the size or quality of the homes; some had giant lawns and sports cars in front of them, while others were small with peeling paint.

The Nashua inhabitants, on the whole, practice polite refusal. Most of them are used to aggressive political campaigns, and would answer the door with resigned sighs and weary faces. They didn’t have much of an accent that I could hear, but their phrases didn’t seem quite like those in Massachusetts. One woman, angry about our candidate, claimed, “There’s not a snowball’s chance in hell that I’ll vote for that woman.” Here in Watertown we don’t hear much about snowballs in hell.

We “nodded” the snowball comment away. We just nodded, thanked her for answering the door, and told her to have a good day. Many of the people we canvassed were Trump supporters, or even registered Republicans.

One tall man with graying hair opened his door and gave us hard, probing looks. He could see from the stickers we wore that we were canvassers for the Hillary campaign; his eyes narrowed, and he put his face in mine.

I timidly asked if he had thought about the election, and he announced in a hard, angry voice that he would be supporting Trump. Just like with the “snowball” lady, it’s never good to get into a confrontation, or heated argument, with a potential voter, so I thanked him, told him to have a good day, and took a few steps off his porch.

As we were walking away, we heard, “You have a good day, too!” come flying at our backs with great volume, and we were unsure what the intent of his statement meant.

After finishing with the houses we had on that street, we walked back down, passing that man’s house again. As we passed, he was attaching an American flag to the outside of his house, now identical to the houses on either side of him. We said hello to him again, and he replied with what sounded like a hearty hello.

Going past his house again, we saw a Navy doormat. He was a veteran. Zev and I could not decide what we thought of the man, his political reaction, or his political identity.

Another house, we didn’t even knock on. It was at the end of a dead end. The door was in an alcove, which meant you had to walk in one door to reach the next one. The lawn was covered with fake, plastic deer, and a number of fake, plastic, automatic rifles. Inside the house, we could hear a dog growling.

Thinking back on the experience, we should have knocked anyways; to refuse to communicate with someone in that manner, is to abandon them from the political process. At the same time, Zev and I were a little frightened. Gun laws and norms are different in New Hampshire, and although there are certainly a number of responsible gun owners, I have run into men and women who yell and bluster when I bring up the subject of the Democratic Party.

One door that we knocked on was opened by a man who yelled out in Spanish to another man in the house. The second man, older, came to the door saying that no one in the house spoke English, and Zev knew only a few words of Spanish.

Fortunately, I took Ms. Berardinelli last year in Spanish, and Ms. Prange the year before that. I reassured the man of my language skills, and launched into a fractured pitch for Hillary and the rest of the important candidates running for races like the Senate and Congress. To my surprise, he responded with enthusiasm for my cause.

Soon, the conversation drifted from politics and voter registration to my experiences in Cuba and my proficiency in the language. When it was time to go, after seven or so minutes of Zev standing around awkwardly, I said emotional goodbyes to my new Democratic, Spanish-speaking friends.

At one point, we walked by a triple-decker house, uncommon in Nashua, looking for a woman named Mary who was a targeted voter on our list. The screen was closed but the door was open. After we rang the doorbell and nothing happened, we rang it another time and walked around the house.

A low gravelly voice called out to us, calling us over, and we saw the body that went with it. The man was short and thin, with a long and unruly beard. His eyes were bloodshot and he was smoking a cigarette. His jeans were ripped and his jacket clung to his body. The protocol while canvassing when you find a registered voter while canvassing who is not the person you’re looking for, you are supposed to talk to them about the election, just don’t check any boxes for them.

We gave the man the spiel, asking him if he had made up his mind about the election, if he knew where his polling place was, etc. He stared at us for a few moments. “If Donald Trump wins, we’re gonna go to [expletive] war. I don’t know where, but it’s gonna be [expletive] war, and you two are gonna be drafted,” he said.

I swallowed, nervous, but went along with what he was saying; I reaffirmed my opinion that Secretary Clinton was a top-tier diplomat, and that Mr. Trump had less foreign policy experience.

“I’d vote, for sure, but I’m not registered,” he said. “No one in this house is registered.”

Excited to win a vote, and maybe more than one, we told him about the town clerk’s office and gave him the information written down. We left the property feeling exhilarated, feeling powerful.

One of our last houses also had the screen closed but the door open. I rang the doorbell, and I could see through the screen a young girl, maybe 5 or 6, running up to the screen, looking at me, then calling for her father. He came, albeit slowly, and opened the door with an inquisitive expression. I told him who I was looking for — it happened to be his wife, who was out getting her hair cut — and he asked me who I was, what I was doing. I told the man that I was volunteering for the Hillary campaign, and he revealed an almost mournful face.

“Sorry, man. I think our household will be supporting the other guy,” he said.

I told him it was no problem, to have a good day, and I almost left when I heard a sharp, high, voice: “How do you know my Mom’s name?”

The little girl was standing by her father, looking up at me with bright eyes and a big smile. I told her that I was canvassing for a person for president, and that her mom was on my list. She didn’t press the matter any further, but I noticed that her father was wearing a Red Sox shirt. I commented on it, and then made the joke that “Hillary likes the Sox! Vote for her!” The man smiled, laughed, and shook his head.

“Have a good day. I like what you’re doing,” he told me.

I smiled back, waved to his daughter and him, and walked to my next house.

When we were done, we put our materials in alphabetical order and drove back to the Nashua headquarters. We gave our lists to the staff, and grabbed a few snacks and water bottles on our way.

I posed a picture with a cardboard cutout of Hillary, said my goodbyes, and we left. When I got home, I collapsed into bed and threw on my Social Justice soundtrack on Spotify. When I woke up, the music was still playing loudly beside my bed.

–Oct. 5, 2016–

Kerri Lorigan • Oct 10, 2016 at 4:14 pm

Jeremy, I also really enjoyed this article. Honestly, I’ve always been intimidated by canvassing, avoiding that aspect of campaigning at all costs. Your experience makes it sound like a wonderful experience and clearly, an opportunity to influence people (even if it’s simply that opponents can be decent people). Thank you for your contribution to the democratic process and to civil discourse (something we desperately need these days).

Ms. Lorigan, WMS

Ms. Riling • Oct 5, 2016 at 11:21 am

It’s probably bad journalist training for you to have nice comments on your article, but I gotta say I really loved reading this! I feel like I really have a sense of what canvassing was like, and I’m impressed by how openminded and confident you and Zev were.

I’m also glad you didn’t go into the house with plastic guns all over the lawn. Sounds like a wise choice to me.

-Ms. Riling

Candace Miller • Oct 5, 2016 at 10:49 am

Jeremy,

What a terrific article! I’ve canvassed in NH before too and your description makes me feel as though I was right there with you. Kudos to you for your efforts, your openness to talk to everyone, your Spanish skills, and your great writing.

All the best, Candace